press archive

photo credit: Eloise Fuss for ABC Arts [January, 2024]

features & profiles

articles & exhibition reviews

features & profiles

Basta Magazine

Feature by Iker Veiga

21 aug. 2025

As It Is Now marks Messums’ first New York exhibition, an ambitious group show that encapsulates the UK-based gallery’s long-standing commitment to art that engages with the environment and strives for sustainability. Opening September 2, 2025 in Detour gallery, and running for nearly two weeks, the exhibition brings together works by Sammy Hawker, Tuesday Riddell, Tyga Helme, Laurence Edwards, Jelly Green and Yan Wang Preston. The show will be presented adjacent to a retrospective on Peter Brown and his paintings of New York, underscoring founder Johnny Messum’s mission to connect international audiences with artists from the UK and Australia. With established locations in Wiltshire and London and a new site opening in Lowestoft in 2026, this New York display brings a piece of Messums’ ethos to the American metropolis, deepening their transnational dialogue between art, ecology, and place.

The exhibition title, As It Is Now, is declarative, yet elusive. It conveys a sense of urgency that appears omnipresent, yet out of reach to the viewer. In what way “It” is, or “It” may manifest itself becomes a question for gallery-goers to complete. What’s evident is that Messums’ show promises elucidation on the state of current affairs, a deep dive into a corrupted zeitgeist defined by the climate crisis, while also eliciting imaginings of what “It” may eventually look like. Messum’s perspective is not fatalistic, but rather open-ended, gesturing towards an alternative future away from the Anthropocene. It is through Sammy Hawker’s work in particular that one begins to see Messums’ guiding philosophy take visual and conceptual form.

Sammy Hawker, a photographer and multimedia artist based in Australia, works primarily on Ngunawal/Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country. As a graduate with honors from Sydney College of the Arts, Hawker has exhibited widely across Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and New South Wales (NSW). Her work has been collected by the Canberra Museum & Gallery, the ACT Legislative Assembly, Canberra Hospital, Goulburn Regional Art Gallery, and Muswellbrook Regional Arts Centre. She began her career working as a documentary filmmaker for arts and environmental organizations, later incorporating photography and chromatography into her independent practice. Over time, she developed a personal and experimental visual language rooted in a deep connection to the land and a concern for ecological balance. Her process is grounded in what she calls “facilitated acts of co-creation” with nature. Whether it be developing photographs using natural materials or facilitating the expression of spectrums of color from organic matter through chromatography, she constantly challenges the limits of human control and proposes an ethic of reciprocity with the natural world through artmaking.

In her oeuvre, the personal and the natural are inseparable. Her environmental commitment took form while living on a bush property an hour north of the ACT, an area affected by both Eucalyptus dieback and the 2019/2020 Black Summer Fires. This experience awakened not despair, but a growing attunement to the resilience of Australian ecosystems. Over time, she came to recognize nature’s cyclical logic, its capacity for destruction, transformation, and regrowth. For Hawker, conceiving ecosystem collapse as final is rooted in an anthropocentric, linear worldview. Her work resists that perspective, instead portraying the environment’s regenerative possibilities, and postulating that nature needs to be approached with care and humility. Her goal: “to draw people’s attention to the natural world, and for people to really consider the sentience of beings and places—outside of a loud capitalist mindset.” Hawker’s practice emerges from a space of surrender and respect for natural processes. However, rather than evoking passivity, this submission to the elements and the processes of organic matter remains intellectually engaged. Her work intends to dismantle ideological myths of human dominance and to open up space for new modes of relating to the world that consider the role of the ecosystem in and of itself.

Her introduction to Messums came through The Corridor Project, an artist residency on Wiradjuri Country in regional Australia, designed to engage the land as both subject and medium. Having grown up nearby, Hawker already had a strong connection to this area, which has deepened through her visits to The Corridor Project over the years. This residency experience has helped define her exploration of interspecies and intercultural relationships. “I think all those different threads have helped inform my sense of seeing the unseen things in the land,” she explains, crediting both scientific methodologies and the energetic, relational knowledge shared with First Nations collaborators, as intrinsic to her practice.

Through these exchanges, Hawker developed a nuanced, postcolonial awareness in her work, recognizing the labor, knowledge, and wisdom of Australia’s Indigenous communities, and the importance of not reproducing colonial dynamics of appropriation as an artist. “Any artist working with Country needs to both listen and remain in evolving dialogue around their approach to a respectful place-based practice.” she says.

One of Hawker’s most characteristic techniques is chromatography, a method she uses to facilitate the visual expression of vibrant matter without human interference. After experimenting with seawater to develop photographs, she turned to this botanical technique to analyze soil and organic matter, to draw out pigments from different materials and beings and create abstract compositions that express their chemical essence. These pieces result in circular cutouts that resemble woodcuts, each one a distinct, infallible, haunting portrait of a being as a spectrum of color. Often, as in one of the pieces on display at Messums, her subjects are deceased beings, such as caterpillars, which are gently honored through her process of chromatographic immortalization.

Chromatography, in Hawker’s hands, becomes a kind of requiem, a post-mortem metamorphosis that distills the subject into its elemental components. These pieces are at once memento mori and meditations on the intangible, infinite, and mutable nature of existence. Her work gestures toward a spiritual unity and an unseen connectivity residing in every insect, tree, and molecule, revealed only through an interaction between natural and scientific-humane processes. And this connection can only be resuscitated through careful inspection and in-syncness with her art as a viewer.

Sammy Hawker’s work embodies Messums’ invitation for viewers to slow down and see differently: to reimagine their place in a global ecological web. As It Is Now hopes to cultivate moments of reflection amid urban pace; to remind us of where we come from, and what we could head towards, of our interconnectedness with the environments we inhabit and affect. Through Hawker’s work and the broader exhibition, the gallery asks audiences to confront the present honestly, but also help build a more reciprocal and regenerative future. From Basta, we can’t wait to visit the space and learn more about the artists on view in a few days. — feature by Iker Veiga.

Art Guide

Feature by Camilla Wagstaff

9 jul. 2025

Sammy Hawker’s acts of co-creation: When Kamberri/Canberra-based artist Sammy Hawker heard that her award-winning work Mount Gulaga (2021) had haunted a prize judge’s dreams, she wasn’t surprised. Her works have a history of whispering, shimmering, and visiting people in the night.

Through what she terms “facilitated acts of co-creation,” Hawker gives voice to places, materials, and the more-than-human world. Under her gentle guidance, whale song takes shape, ocean water becomes collaborator, salt crystals scatter themselves like stars across analogue film, and ashes murmur secrets onto silver nitrate-soaked paper.

Her processes are unpredictable. Her outcomes feel like conversations—images formed through intuition, trust, and deep listening. “There is a sense when a material wants to make work together,” Hawker says. “There is a feeling of alignment or serendipity often accompanied by a visceral sensation, like a shiver down the spine.”

A recent shiver involved Humpback Whale Migrating South (2024), one of the centrepieces in Hawker’s exhibition at Tweed Regional Gallery, on Bundjalung Country in northern New South Wales. The image was photographed on 35mm film and processed using ocean water collected at the site. “When I took the photographic negative out of the jar of ocean water, I couldn’t help but smile at how much its visual contribution seemed to reflect the whale’s playful resonance,” she says. “A sweep of salt residue across the middle of the photograph resembles the outline of a dolphin. I guess the dolphin didn’t want to be left out of the image!”

Another eerie example involved Dark Crystals (2021), which began appearing in a close friend’s dreams after she saw it on exhibition. Like Mount Gulaga, the work was processed with ocean water collected from Walbunja Country (Yuin Nation). “We later realised Dark Crystals was created on and with the same place she had spread a loved one’s ashes,” says the artist.

Mount Gulaga, 2021

Dark Crystals, 2021

At the heart of Hawker’s practice is her unwavering commitment to reciprocity, “a practice of exchange—to give and receive in a balanced way,” she explains. It’s a concept that has shaped her work since her honours year at Sydney College of the Arts in 2015, under the supervision of Bianca Hester. Since then, she has participated in a range of initiatives exploring cultural competency and reflexive collaboration, including Catchment Studio, The Corridor Project, Bundian Way Arts Exchange, Plumwood Inc., and The Fenner Circle.

Hawker’s process takes time, ongoing conversations, and a meaningful connection to place. An essential part is building relationships with Traditional Custodians and local ecologists who care for the Country she works with. “I do my best to work respectfully; treading lightly, donating profits from artwork sales back to Country, working in alignment with Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) protocols, and remaining open to how I can continually fine-tune a respectful approach to a place-based practice,” she says. “I’ve been advised by various custodians to ‘ask Country’ when working on or with it. To ask and to listen are essential components of a reciprocal relationship.”

This ethos ripples and flows through her Tweed show, which follows the humpback whale migration cycle along the east coast of Australia. The exhibition features two central bodies of work: 35mm film photographs like Humpback Whale Migrating South, and a series of cymatic images—visual representations of whale song created using a bespoke instrument that translates sound vibrations into form. Developed in collaboration with Kamberri/Canberra-based designer Sam Tomkins and drawing on recordings by Mark Franklin of The Oceania Project, the resulting images are hauntingly abstract and pulsing with presence. “It’s been a joy to work on,” says Hawker. “So many late nights fine-tuning the cymatic instrument in the studio, whale song emanating around me like a dark glittering fog.”

In October, Hawker embarks on an international residency as part of a cultural exchange between The Corridor Project (Wiradjuri Country) and Messums Org (UK). Coinciding with the residency is her solo Ghosts [& Monsters] at Messums West in Wiltshire, UK—a gallery housed in a restored 13th-century barn. Come mid-2026, she presents work developed during the coming residency at the launch of Messums East, a gallery and cultural centre in the former Post Office building in Lowestoft, UK. Later next year, a major survey of Hawker’s practice will be staged at Orange Regional Gallery on Wiradjuri Country in New South Wales.

While exhibitions and accolades are important, for Hawker the real reward lies in how her work communicates—often in unexpected or uncanny ways. “When reflecting on my practice, I think a lot of what I make comes back to our society’s resistance towards the natural processes of time, gravity and death,” she says. “I think about how disintegration can also be thought of as metamorphosis. There’s a beauty in surrendering our need for constant control, instead accepting these processes as part of the human, and post-human, experience.”

Much like whale song, Hawker’s works resonate long after they are experienced. Her practice invites us to slow down—to consider the quiet intelligence of matter, memory, and the more-than-human world. — feature by Camilla Wagstaff.

ABC Arts

profile by Eloise Fuss

11 feb. 2024

It's the middle of Summer in Sydney, but a cool change is sweeping through as visual artist Sammy Hawker sets up a tripod on the blustery harbour foreshore. Atop it, she balances a large-format film camera — Hawker is well-practised at working with the elements. She sets up her shot, a moody ocean-scape, and pulls a striped towel over her head. With one precise click, she captures the scene on a single slide of negative.

Hawker is known for her experimental photography. She "co-creates" artworks with elements of the natural environment and found materials within it. She has previously encrusted film negatives in honeycomb, used caterpillar remains found in a trough to produce butterfly wing-like forms, and used analogue techniques to give a second life to human ashes.

Her current project, titled [holding] space, seeks to share some of that creative licence with the iconic, chronically over-photographed Sydney Harbour. She collects saltwater from the harbour to help develop the film, which corrodes and marks the negative to compelling effect. "The more that I continue working with different materials, the more I see that materials have memory or hold memory and there's a kind of resonance inscribed within them of what has come before," says Hawker. "The beautiful thing about being an artist is that, maybe there is no way I can scientifically prove that, but you can suggest it through working with the materials and showing the work. It's more this kind of punk science [and the] soft suggestion that something might be there."

Stories in sediment: Hawker has long been fascinated by Sydney Harbour, on Gadigal and Birrabirragal Country. Her work is informed by conversations with traditional custodians, scientists and researchers, and draws on the rich sediment of the harbour — from its sandstone bedrock to its colonial history — to unearth "memories". The sandstone Sydney is built upon formed from grains of sand, derived from rocks that existed between 500–700 million years ago, Hawker explains. "[It's] made up of individual grains of silica sand that had travelled in a river from what's now eastern Antarctica, and [at the time] Sydney was a swamp, so it kind of got stuck here and formed this rock. But I've always had this feeling that sandstone feels really living and it has this kind of presence to it. It doesn't feel static."

From the geological to the topographical and historical, Hawker is also interested in the history of Sydney Harbour's water and its role as a "holding space". "Sydney Harbour itself was a river — what's now known as Parramatta River — but in the last Ice Age, which was 10,000 years ago, the ocean water rose and that's when it became a harbour," says Hawker. "[In this project], I'm looking at the idea that water is a carrier of memory, particularly this harbour water. "[It] circulates slowly around [Sydney] Harbour and carries these memories — everything from the dark history of colonisation, to the tributaries and dendritic patterns that used to run through estuaries and the river underneath, to the fact that the ocean water was created with comets and solar dust, and that kind of interstellar resonance, which appears on the photographs."

The power of old film: To capture these ancient stories, Hawker shoots on old film cameras — both large and medium format — and employs laborious analogue processing techniques. "The cameras have their own stories," says Hawker. "I really like working with film because [it feels] like a canvas and a really beautiful material to work with. Coming from a digital documentary and video background, there's been something so nice in using my hands to make a photograph, rather than take a photograph."

After finishing a roll of film — roughly 10–12 images in medium format — Hawker hands me her camera, picks up a jar and wades into the ocean. She fills the jar with briny water, which she'll use later when she processes the roll.

Processing in saltwater: Sitting on Woollahra's Redleaf Jetty, I watch Hawker feel her way around a black bag with armholes as she carefully transfers the light-sensitive film into canisters. This process is usually done in a darkroom: if the film sees light before developing, it becomes overexposed and turns out blank. But with Hawker's black-out bag — her makeshift darkroom — she can process film on location. "I really love it because my whole practice is about working with site and I think there's something in processing [in that environment] that's so much nicer."

Once in the canisters, Hawker uses three chemicals to process the film. First, she immerses it in a developer (pre-mixed with harbour water), then a stop bath solution to halt the developing process, and a fixer, to affix the image to the negative.

"Film is basically an alchemy of light and time," Hawker explains as she works.

"When you're taking a photograph, you think about the shutter speed, the aperture and the ISO, depending on the light conditions, so it's the same thing when you're processing film. "The process is kind of fixing the image that you've taken through the camera onto the film. But then I put the image back in the jar of the harbour water, and the fixer doesn't really do his job because the harbour water takes the image away again. There's a conversation between the fixer and the harbour water I guess."

In the jar, the harbour water begins to corrode the image, leaving curious imprints and patterns. "[There's] this feeling that it's breaking open the four walls of the frame and making its mark; adding its own voice to the process," says Hawker. “I've just had such consistently beautiful results, and the more that I work with it, the [more] recurring patterns will appear … like these crosses that come up from time to time. To me, they're a sign of sentience or a kind of presence. There's this real feeling whenever they appear, the photograph has a lot of power to it."

Punk science: Before we look at the developed images, Hawker shows me the other project she's been working on as part of her residency with Woollahra Gallery at Redleaf (Gadigal & Birrabirragal Country). She's experimenting with chromatography, a technique invented by a Russian-Italian botanist in the 1900s, involving separating plant pigments using chemicals. Today it is used widely in agronomy by scientists and farmers to check soil quality, explains Hawker. As the chemical compounds of the matter separate on round filter papers, different colours, forms and patterns appear. "They're just amazing, they're so varied. You can't predict how it's going to turn out," says Hawker.

The film reveal: On the jetty at dusk, Hawker strings up her final shots: glimpses of sandstone, harbourside trees and ocean shores filling her square frames. But while Hawker's take is captured, it's time to let the salty harbour water, sloshing below us, have its say. "If an image is interesting, I'll scan it in just to have a record of it, and then I'll put it back in a jar of the harbour water and allow that kind of corrosion process to continue," says Hawker. "The image generally goes through various states of deterioration until I arrive at a point, which is really beautiful and magical. Sometimes they just disappear completely and there's nothing left, but that's all part of the process." — article by Eloise Fuss.

Art Collector

Profile by Jo Higgins

Issue No. 107 | jan. — mar. 2024

Sammy Hawker's photographs hum and crackle and whisper with a compelling sentience that evades most ordinary landscape images. But then Hawker's photographs are anything but ordinary. Less a photographic practice than a process of facilitating what she describes as the voices of the materials and places she's working with, Hawker's images are acts of co-creation, active listening and immersion, literally. Hawker's 35mm film images - many of her surrounding Ngunawal/Ngunnawal/Ngambri + Walbunja/Yuin Country - have been developed in water that Hawker collects from the ocean or nearby bodies of water. Interested in the expressive capabilities of salt, these unique chemical interactions with the surface of the negative evince previously unseen constellations, murky swirls and mesmerising geometric, crystalline patterns over the surface of these landscapes. Other negatives are processed further with the help of bees.

As Kirsten Wehner, James O. Fairfax Senior Fellow in Culture and Environment at the National Museum of Australia & former Director of Canberra's PhotoAccess has observed, "Sammy is less interested in showing the world as image and more interested in producing artefacts that are inseparably part of the world, and which embody within them the forces of time and chemistry and light distinctive to particular places in the world."

Hawker's sensitivity and care for these acts of co-creation includes relationships with traditional custodians, scientists and researchers. Relationships that, like her images, are nurtured and given time.

Asking questions of our relationship to place; considering how to make meaningful work with Country as a non-Indigenous artist; quietly imploding colonial landscape traditions and the legacy of the singular frame, Hawker's works are invested with time and create space for the contemplation of immaterial presences, not-knowing and wonder.

Little wonder then, that momentum is gathering for Hawker. Her work has been collected by the Canberra Museum & Gallery and the ACT Legislative Assembly and is receiving increasing recognition. In 2022 she was awarded the $15,000 Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize and in 2023 she received the Canberra Contemporary Photographic Prize and was a finalist in both the Bowness Photography and Ravenswood Australian Women's Art Prizes.

This year is also looking to be busy for Hawker. There's a summer residency at Sydney's Woollahra Gallery at Redleaf, funded by artsACT, and her announcement as one of 14 finalists in the National Photography Prize at MAMA Albury. There is also a group exhibition at Canberra Contemporary Art Space in February and research and relationship building towards residencies and significant solo exhibitions at Orange Regional Gallery and Tweed Regional Gallery in 2025. Luckily, with all this buzz, Hawker's practice of moving slowly and with care will be sure to keep her grounded. — profile by Jo Higgins.

ABC Art Works

produced by Richard Mockler

Series 3, 2023

Sammy Hawker is a Canberra-based visual artist who collaborates with insects, oceans and rivers to create unique photographs. Most recently she has used beehives as part of her process, letting bees create hive patterns on top of analogue film of landscapes. By inviting in these more-than human forces to interact with the negative, she disrupts her authorial control over the image. Moving beyond just capturing a moment, her photographs can be seen as conversations with landscape. — produced by Richard Mockler.

Wonderground Journal

Issue No.4 | 2022

My works takes me to places where a quiet magic resonates; where the water leaves the blood sparkling in your veins; where the horizon disappears and the sound of nothingness compresses around you. Places where you lie on your back and feel the relief of your insignificance under the brittle diamond stars.

In a conversation with American journalist Ezra Klein, author Richard Powers, whose books include The Overstory and Bewilderment, describes this feeling as one where the scales fall from your eyes. Moments where your sense of meaning shifts from an inward-facing self-narrative to a wider perspective which accounts for other ways of being. As he states: ‘when you make kinship beyond yourself, your sense of meaning gravitates outwards into that reciprocal relationship, into that interdependence.’

In my creative practice I am interested in how I can facilitate acts of co-creation with these other ways of being; to give voice and visual expression to the more-than human worlds that vibrate around, and within, us. It requires surrender to the unknown. A dance of trust, where I break open the frame of the photograph and relinquish my authorial control. The materiality of analogue photography is a perfect canvas to co-create imagery; whether it be soaking film in ocean water, leaving negatives in beehives or substituting seaweed as a developer. The results are vibrant experiences of reciprocity where I am constantly awed by the logic behind the marks made by these more-than human collaborators.

When I exhibit these works I am similarly intrigued by the way they communicate with their audience. I’ve had various reports of visceral responses including crackling or tapping sounds, ASMR type tingles, the works reappearing vividly in dreams and eerie synchronicities, such as a work communicating a message from a loved one that has passed. I’ve come to think of these ruptured photographs as portals to a deeper frequency that resonates beyond our rational state. An invitation from these other ways of being to let the scales fall from our eyes.

Murramarang NP #1, 2021, archival photographic print from 6 x 6 negative processed with ocean water and hailstones.

Hawkcr, Murramarang National Park #1, 2020.

This image was taken on Yuin Country just after a hailstorm passed over my campsite. I developed the film on a picnic table by the beach using hailstones and ocean water collected from the site. It feels as if some of the storm’s energy found its way into the work. A kaleidoscopic presence hovering above a forest of spotted gums. Many people have had quite a visceral reaction to this work. It seems to communicate a type of crackling sound - perhaps the sound of rain freezing into hail?

Melt, 2021, archival photographic print from 6 x 6 negative processed with open flame.

The image was taken six months after bushfires passed through Bush Heritage’s Scottsdale Reserve, south of Canberra. The photographic negative was later exposed in the studio to open flame. To me, the heat of the flame reveals a subterranean energy, a deeper frequency that hovers beneath our rational conscious state, present when we centre ourselves enough to tune in. I have been very fortunate to spend time walking Scottsdale with Ngunawal custodians Tyronne Bell, Jai Bell & Phil Carroll while they conducted a post-fire cultural heritage survey of the land. Their care and attunement to Country has greatly heightened my own experience of living and working with the Australian landscape. — words by Sammy Hawker, edited by Georgina Reid.

Paradiso Magazine

Issue No. 19 | may — jun. 2021

It was at the end of last summer I took a roll of 35mm film from the Easternmost point of Australia (Bundjalung Country). It was mid-morning and the light was bright with a line of musing clouds forming half-heartedly on the horizon. The next week I processed this film using a jar of Byron Bay ocean water which travelled via courier on an inland migratory journey from the Northern Rivers to my red-brick apartment in Canberra's inner-north.

When processing film with ocean water the corrosive properties of the salt breaks open the permanency of the photograph. The ocean water lifts the silver emulsion and the representational image is rendered vague. However an essence of the site is introduced to the frame as fractals form on the horizon and salt crystals appear around the disappearing edges. To me it feels the image becomes alive; the ocean water an example of vibrant matter which paints its way onto the negative.

A psychedelic take on a Sugimoto seascape. A glittering, mysterious, collaborative self-portrait.

Acts of co-creation are never predictable and the resulting images can be unsettling. They challenge concepts of memory and preservation while awakening a yearning to capture some type of deeper feeling that proves both slippery and indefinable. Haunting the borders of certain moments but existing at the liminal edge of a vanishing image - always just beyond grasp. It is, as Bill Henson put, 'the same thing which draws you in, is the thing that slips away.'

Through facilitating acts of co-creation in my practice I am interested in decentering my position as the artist while recognising and celebrating the agency of the more-than human. The concept of the ‘more-than human’ does not only refer to other living beings but extends to include all forms of matter. As Jane Bennett considers in her book Vibrant Matter, what are the political implications of recognising matter that exists outside of us - including oceans, mountains, forests, storms and even methane producing rubbish tips - as not passive or inert but rather as 'forces with trajectories, propensities or tendencies of their own.’

This position is what writer Charles Eisenstein would describe as a 'deep radicalism' where we are encouraged as humans to not see ourselves as separate of the other but rather embracing, as philosopher Michel Serres envisions, a new ecology based on a postcolonial equality between the human and more-than human. While many First Nations cultures understand this perspective, the infrastructure of modern Western societies validates domination and control over the natural world, rewarding the conceit of the individual and systems of mono-cultures. However the fantasy of individual autonomy is thinly veiling the fact that even the human body belongs to an entangled world of symbioses where cross-species confluences is a near requirement for life. As Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan and Nils Bubandt ask in their text Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet ‘How can we repurpose the tools of modernity against the terrors of 'Progress' to make visible the other worlds it has ignored and damaged. Living in a time of planetary catastrophe thus begins with a practice at once humble and difficult: noticing the worlds around us.’ Accepting, celebrating and collaborating with the other cultivates empathy and is a responsible way of moving forward in an age of environmental crisis.

This shift in world-view invites an awareness of how we hold ourselves in space. It welcomes a more intuitive stance - one that asks us to slow our frequency, breath more deeply and observe that which exists quietly in the shadows. In her essay Experiencing the Intangible, trans-disciplinary artist Maja Kuzmanovic describes her grounding process when preparing to work within a new site. 'I meditate on extending the membrane of my subtle body beyond the physical one. With every in-breath, I visualise my “self” shrinking, and my skin becoming a reflective surface. With every out-breath, I “unfold” my membrane to include the people around me, the room, the village, even so far as the Laurisilva [laurel forest]. By the end of it, I feel thin and translucent, shimmering like a beech forest in the early spring.' The recognition of one's energy field, otherwise known as the 'subtle body', as extending beyond the visible confines of one's skin is a moment of tangible recognition of the effect of our every action. It also places us in a more receptive position to recognise other energy fields and cross-species entanglements that are in constant motion around us.

Biologist Andreas Weber’s concept of ‘erotic ecology’ puts forward the notion that every ecology centers on the principle of attraction with love being an impulse to establish connections and intermingle with the other. As he states, ‘experiences of reciprocity allow us to feel both our own life and that of the world in a new, delightfully intense way.’ I have personally experienced this in my recent practice, moments of almost unbridled joy at the results of co-creation with unpredictable elements. It is sitting with the discomfort of the unknown, surrendering to the unresolved mystery of the ocean and the dark energy that interrogates and transforms the photograph. It is the feeling of quiet curiosity in recognising the other as a vibrant force, full of agency and in that choosing love over fear. As ethnographer Deborah Bird Rose writes in Shimmer: When all You Love is Being Trashed, humans have the capacity for both violence and care and in this time of mass-extinction we are going to be ‘asked again and again to take a stand for life, and this means taking a stand for faith in life’s meaningfulness.’ Choosing love is to embody empathy both for ourselves and others. It requires us to forgo the Western notion of the autonomous individual, separate from other, and to instead embrace our place within the messy vibrant entanglements that exist both within and around us. As Weber writes, ‘…only by relearning to understand our existence as a practice of love will we grasp anew the overwhelming ecological and human dilemmas that we face…and find the means to deal with them differently than we have thus far.’ — words by Sammy Hawker, edited by Anna Hutchcroft.

articles & exhibition reviews:

Artist Profile

Review by Emma Walker

Issue No. 73 | nov. 2025

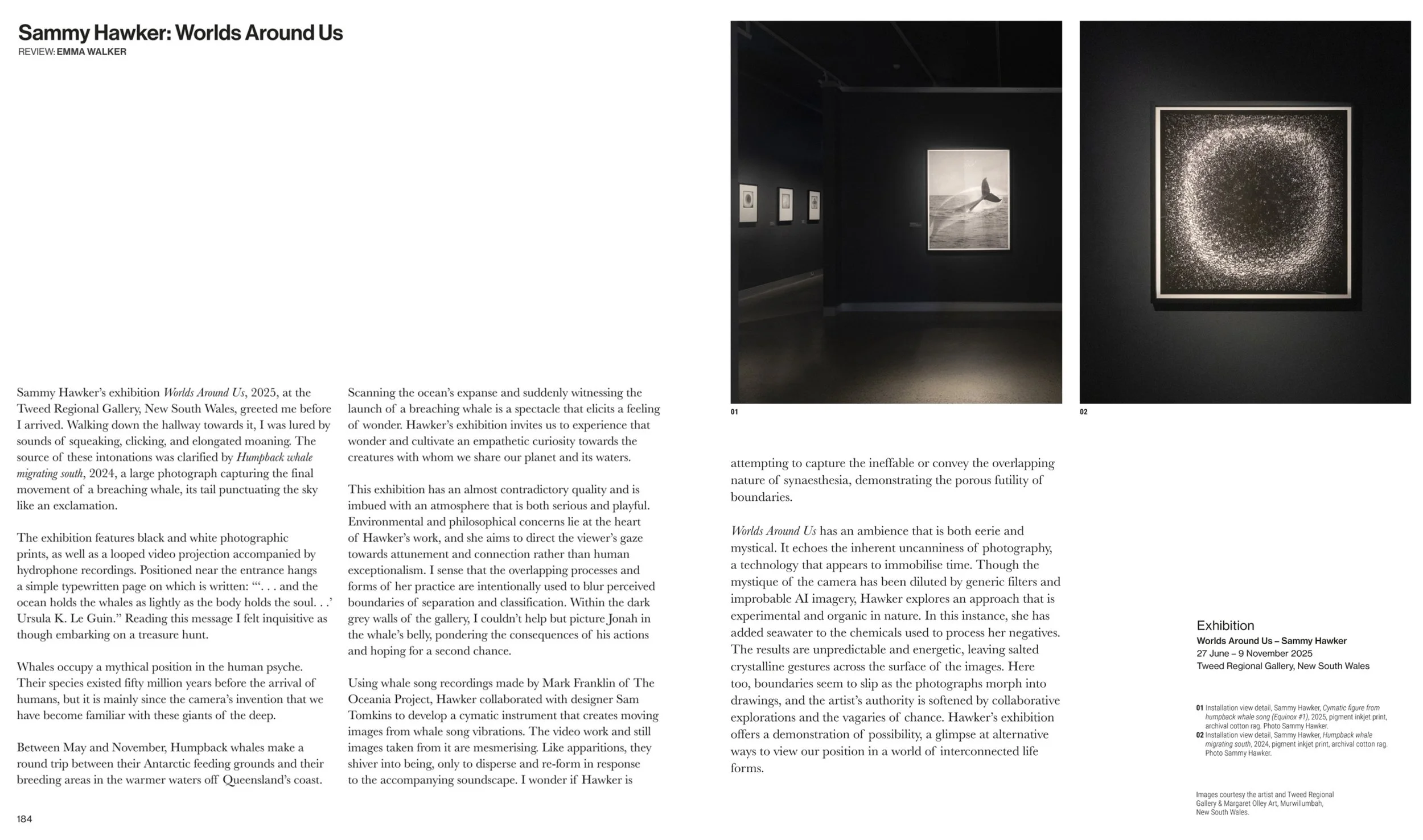

Sammy Hawker's exhibition Worlds Around Us, 2025, at the Tweed Regional Gallery, New South Wales, greeted me before I arrived. Walking down the hallway towards it, I was lured by sounds of squeaking, clicking, and elongated moaning. The source of these intonations was clarified by Humpback whale migrating south, 2024, a large photograph capturing the final movement of a breaching whale, its tail punctuating the sky like an exclamation.

The exhibition features black and white photographic prints, as well as a looped video projection accompanied by hydrophone recordings. Positioned near the entrance hangs a simple typewritten page on which is written: "... and the ocean holds the whales as lightly as the body holds the soul…Ursula K. Le Guin." Reading this message I felt inquisitive as though embarking on a treasure hunt.

Whales occupy a mythical position in the human psyche. Their species existed fifty million years before the arrival of humans, but it is mainly since the camera's invention that we have become familiar with these giants of the deep. Between May and November, Humpback whales make a round trip between their Antarctic feeding grounds and their breeding areas in the warmer waters off Queensland's coast.

Scanning the ocean's expanse and suddenly witnessing the launch of a breaching whale is a spectacle that elicits a feeling of wonder. Hawker's exhibition invites us to experience that wonder and cultivate an empathetic curiosity towards the creatures with whom we share our planet and its waters. This exhibition has an almost contradictory quality and is imbued with an atmosphere that is both serious and playful.

Environmental and philosophical concerns lie at the heart of Hawker's work, and she aims to direct the viewer's gaze towards attunement and connection rather than human exceptionalism. I sense that the overlapping processes and forms of her practice are intentionally used to blur perceived boundaries of separation and classification. Within the dark grey walls of the gallery, I couldn't help but picture Jonah in the whale's belly, pondering the consequences of his actions and hoping for a second chance.

Using whale song recordings made by Mark Franklin of The Oceania Project, Hawker collaborated with designer Sam Tomkins to develop a cymatic instrument that creates moving images from whale song vibrations. The video work and still images taken from it are mesmerising. Like apparitions, they shiver into being, only to disperse and re-form in response to the accompanying soundscape. I wonder if Hawker is attempting to capture the ineffable or convey the overlapping nature of synaesthesia, demonstrating the porous futility of boundaries.

Worlds Around Us has an ambience that is both eerie and mystical. It echoes the inherent uncanniness of photography, a technology that appears to immobilise time. Though the mystique of the camera has been diluted by generic filters and improbable Al imagery, Hawker explores an approach that is experimental and organic in nature. In this instance, she has added seawater to the chemicals used to process her negatives.

The results are unpredictable and energetic, leaving salted crystalline gestures across the surface of the images. Here too, boundaries seem to slip as the photographs morph into drawings, and the artist's authority is softened by collaborative explorations and the vagaries of chance. Hawker's exhibition offers a demonstration of possibility, a glimpse at alternative ways to view our position in a world of interconnected life forms. — review by Emma Walker.

Artlink

Review by Una Rey

11 sep. 2025

[excerpt] — A week after visiting Tweed Regional Gallery the image that has stayed with me is Humpback whale migrating south, (2024)—not strictly a portrait, but the entry point to Worlds Around Us, the outcome of Sammy Hawker’s Nancy Fairfax Artist in Residence at the Gallery's studio. The exhibition fills a darkened space off the main concourse from which each window frames a picture postcard of Wollumbin / Mount Warning. The ‘dark room’ works effectively as a companion show to the Olive Cotton Award for Photographic Portraiture which celebrates 20 years in 2025.

In Hawker’s grainy photographs, salt-crystals leave a residual trace on the grey seascape; in another of the three oceanic scenes, a whale’s tailfin tricks the eye, instantaneously appearing like a black-winged bird taking flight. Such fleeting illusions increase the private pleasure of looking and a metaphorical cliché offers itself as I fly out of Coolangatta days later: a barely submerged whale looking for a moment like a sinking ship registers a more poignant metaphor of collapse. Further south over the Hunter Valley, a vast open-cut coal mine completes the loop.

In concert with Hawker’s romantic quasi-vintage naturalist views, five inkjet prints made from hydrophone recordings of humpback whale song gathered off Australia’s east coast by Mark Franklin of the Oceania Project evoke the loss apparent in the Anthropocene. These monochrome mandala-like images are distilled from recordings using an analogue cymatic instrument. The effect of this underwater chorus and its mechanical reproduction is hypnotic, otherworldly, creating a beguiling art/science collaboration with environmentalist intent.

Hawker is a Canberra based artist and winner of the 2022 Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize, among other ‘contemporary’ and ‘national’ photographic awards, though such categories are not mutually exclusive. As for so many artists, categorisation is a double-edged sword, one that Olive Cotton reflected on late in her life.

I would not like to be labelled a romanticist, Pictorialist, modernist or any other ‘ist’. […] I want to feel free to photograph anything that interests me in whatever way I like. Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton: A life in Photography, (Fourth Estate/Harper Collins Publishers Australia: 2019), 457 — review by Una Rey.

Time Out Sydney

review by Alannah Sue

17 apr. 2024

Beyond the Veil (diptych), 2023, pigment ink-jet print on archival cotton rag. Image credit: Jeremy Weihrauch

[excerpt] — Sammy Hawker’s ephemeral images call to mind the visual echoes of planets, galaxies, and Victorian era ‘aura photography’. The ACT-based artist (Ngunawal/Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country) uses Chromatography, a photographic process invented in 1900 that is primarily used by scientists to understand the chemical makeup of soil. However, Hawker uses the process to create abstract “portraits” from ash or ‘dead’ matter – recording the vibrancy of sources as disparate as drowned caterpillars, a real human placenta, and soil from a grave. Sammy also receives requests from people who wish to memorialise their lost loved ones, and with permission, a Chromatogram created from the ashes of a stillborn baby is included in the body of work displayed at MAMA. Merging the scientific with the emotional and spiritual, ‘Material Resonance [beyond the veil]’ speaks to the energy or memory inscribed within materials; yielding vivid, striking, and eerie results. — review by Alannah Sue.

Canberra City News

article by Helen Musa

13 feb. 2024

Alchemy is the age-old practice of attempting to turn a base metal into gold and by association find the elixir of life. In the arts, however, alchemy has become a byword for turning something ordinary or even scorned into something precious and magical.

That’s exactly what’s happening with Project Alchemy, a multimedia exhibition coming up at The Hive in Queanbeyan, in which, magically the rubble, charcoal and shattered dreams that followed the Black Summer Fires of this region are turned into pure gold. It’s the result of a project Queanbeyan artist Helen Ferguson has been managing on behalf of Canberra social change arts company, Rebus Theatre, working with affected communities – Bega Valley Shire, Eurobodalla Shire, East Gippsland, Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council and the ACT – with three artists selected from each region to “heal hearts and weave magic”.

It’s about to culminate in an exhibition at the “Yellow House”, The Hive, opposite the council chambers in Queanbeyan, where works by the 15 Project Alchemy artists will be seen. Related ventures that followed Rebus-led residencies in 2022 and 2023 have included community dances, walks through fire-devastated properties, eco dying, printmaking, music and chromatogram workshops, tree planting, dance and involvement with events such as The Daring Festival of Possibilities in Bega Valley Shire.

On show at the Hive will be embroidered works and a larger collaborative piece from artist Michele Grimston’s workshops, concertina art books of drawings and paintings from Cecile Galiazzo’s Wonder Walks and a free illustrated handbook, Nye on the River of Life, by artist Sue Norman with Colleen Weir.

A chosen artist from the ACT is Sammy Hawker, a freelance videographer and photographic artist who in her short time here has become almost legendary. A relative newcomer to Canberra, Hawker studied video art at the Sydney College of the Arts, but moved to Canberra and discovered PhotoAccess – “My spiritual home,” she says.

“I learnt how to process film and then lockdown happened. I never saw myself as a photographer, but I discovered that film allowed me to experiment.” She did and has since won a swag of prizes, including the 2022 Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize and the 2023 Canberra Contemporary Photographic Prize. “Photographers are a little bit suspicious of me, suspecting that I might not be a real photographer, and I agree with that,” she says. Hawker’s secret was her discovery of chromatography, invented in 1900 by botanist Mikhail Tsvet, a process for separating components of a mixture to create “the visual expression of vibrant matter”. By using a teaspoon of soil from a site, she could use the chromatography process to help material to express itself. “I tried it with a leaf from a favourite scribbly gum in O’Connor, but it could have been from any tree or a leaf,” she says.

“I put a nine-centimetre circumference filter paper with a little wick, then the silver nitrate solution I had created spread up on the paper, so the paper developed. I blew the images up and saw the chemical make-up coming into a visual expression – the patterns that formed could not be manipulated or controlled.” Hawker is a fire survivor, having been at Bermagui when the fires struck and also residing around that time near Michelago, feeling their direct impact. This gave her the first-hand experience she needed to embark on Project Alchemy.

Her final exhibit for The Hive is not a conventional picture but a composition of 64 printed chromatographs. “People who were recovering from the effects of bushfires came together with stories of strength and sometimes their favourite trees… I worked directly with some of them and others posted me a leaf or a piece of fire litter,” says Hawker. “They told me beautiful stories, including one about how a tree had survived because it was next to a water tank which burst, sending water soaking down to the roots. “I feel together they would make a great book.” — article by Helen Musa.

Region Media

article by Sally Hopman

4 sep. 2023

Canberra artist Sammy Hawker has won the inaugural Canberra Contemporary Photographic Prize – but her winning work goes way beyond that of a simple image. Her evocative work, Caterpillars in Metamorphosis, won her the $2000 first prize in the PhotoAccess competition. The judges, visual artist Anna Madeleine Raupach, photographer Chris Round and director of PhotoAccess, Alex Robinson, described her work as an “exceptional blend of concept, process, and execution”.

The artist, who now lives in Canberra but originally hails from Cootamundra, experimented with the chromatography photographic process to create the winning work. And caterpillars.“One morning, I found these caterpillars drowned in a trough,” she said. “I collected them in a jar, ground their bodies and turned them into a chromatogram. “Chromatography is a photographic process invented by botanist Mikhail Tsvet in 1900.

“While commonly used by scientists to read soil vitality, I’ve recently been testing the process’s ability to facilitate the expression of a wide range of vibrant matter. So far, I’ve had exciting results from human ashes, a placenta, a death cap mushroom (I was very careful!), many varieties of eucalyptus trees, and now with drowned caterpillars.” She said when using the process of chromatography, the artist needed to set aside their expectations. “The hues and patterns that form on the silver nitrate-soaked paper cannot be manipulated or controlled. The process speaks to the resonance and memory inscribed within materials – no matter what stage of metamorphosis they are in.” Sammy said her passion was to work with materials “from site”, experimenting with everything and anything if it inspired her.

Seeing herself more as “a facilitator” than a photographer, she is a keen proponent of the land art movement established by a group of artists in the 1960s and 70s who looked at natural sites and alternative modes of producing art – to circumvent the world of commercial art. Land art is also inherently linked to the landscape, with artists of this genre preferring to use materials from the sites they work from. For Sammy, it was the discovery of these drowned caterpillars – and the decision to process some of her images non-traditionally. “I love the idea of an artist having no control over their medium,” she said. “With some of the negatives, I processed them with salt water. I had no control over the outcome, which I loved. It will express itself however it wants. “I think it is so important to go into an environment and not be the dominant voice. It is so important to let other voices speak.” — article by Sally Hopman.

Canberra Times

review of Salt by Brian Rope

18 feb. 2023

Salt is a new exhibition by ACT-based visual artist Sammy Hawker. Hawker attracted early attention when her work Boy in Versailles was selected by renowned photographer Bill Henson for the 2010 Capture the Fade exhibition in Sydney. That piece was also named the people's choice winner.

Then we were all impressed in 2019 with her video Dieback about the eerie phenomena of mass tree extinction - white gums in the Snowy-Monaro. Along her artistic journey since, Hawker has had significant success.

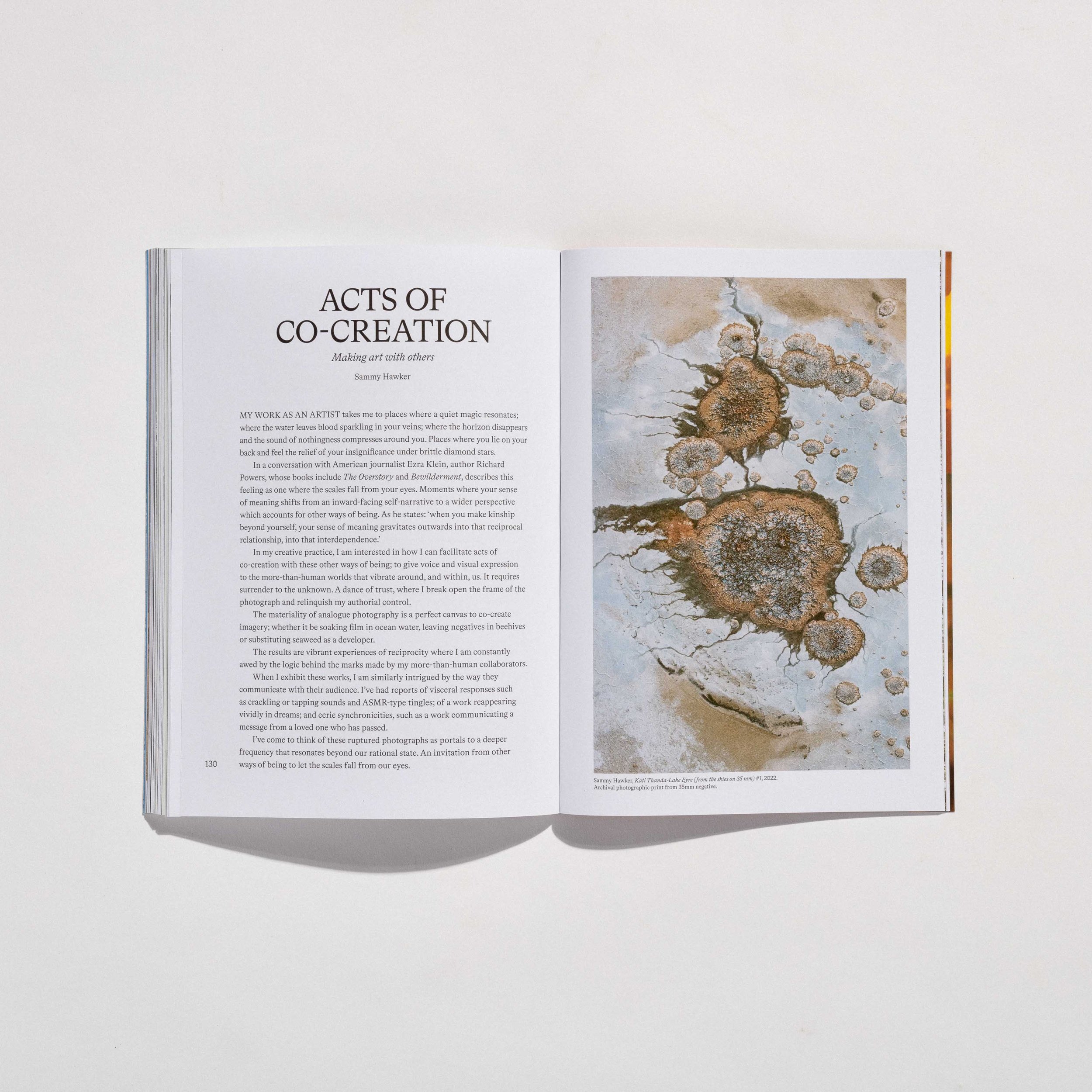

This exhibition once again delivers. As senior curator of visual arts at Canberra Museum and Gallery, Virginia Rigney, said in her opening remarks, Hawker's use of the familiar substance of salt reveals new mysteries. This exhibition includes works from recent trips across Australia, travelling from the east coast (the Yuin Nation and Arakwal Country) to Kati Thanda - Lake Eyre (Arabana Country).

Taking her "studio" with her, she has spent significant time at each location to understand it, then co-created art by processing photos where they were exposed using traces of salt found at the sites to lift the emulsion and alter the documentary images. Hawker speaks of places where a quiet magic resonates; where the water leaves the blood sparkling in your veins; where the horizon disappears - and the sound of nothingness compresses around you.

Hawker's process brings an essence of country into her work, painting its way onto negatives and sharing deep and mysterious forces around us that transform her photo-graphs. The details in Broulee Salt Sketch from 2020 show that very clearly. So too do Did I Dream You Dreamt About Me? and Everything is Waiting for You.

Two Lake Eyre works are among the standout images, Epiphanous and Kati Thanda - Lake Eyre #1, both featuring delicious pastel tones and the latter revealing a selected pattern from high above.

Amongst the black and white images, Everything is Waiting for You and Did I Dream You Dreamt About Me? each pose numerous questions. The latter demanded I grab a phone shot of someone reflected in it, dreamily exploring. And the inclusion of Hawker's 2022 Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize winning work, Mount Gulaga, is a bonus for those who have not previously seen it.

There is also a marvellous collaborative work between Hawker, Jessica Hamilton & Sam Tomkins. It explores the possibilities around generating dialogue between image, sound and form.

Their starting point is Hawker's image, Dark Crystals, a work processed with ocean water at Mollymook, NSW in 2021. Hamilton has a special connection to the place in this image, and was inspired to use the visual data along the horizon line of the image to create a spectrogram. It picked up the varied textures deposited on the negative by the ocean's salt. She then converted the spectrogram into a waveform and processed it through a synthesiser to create a sound piece.

Next, Tomkins designed and created a "chladni plate" to respond to the sounds. When the plate is oscillating with certain frequencies, the salt on top creates distinct patterns. Hawker used an online pitch detector to break down the various notes/ frequencies in the sound piece. Played through the plate, the visual patterns formed - such as 1041.8 Hz - C6 are intriguing. look forward to more exciting outcomes from these collaborators.

The exhibition is more than just printed images. There are negatives on display too and, perhaps best of all, a great journal of Hawker's words along with numerous images worthy of close examination. — review by Brian Rope.

Canberra City News

review of Salt by Con Boekel

23 feb. 2023

One of the more innovative and creative genres in contemporary environmental photography has a curiously retro feel to it.

Broadly, it involves some reversion to analogue processes. This genre is hands-on. The photographers might use soil biota such as fungi, local “dirty” water, or local minerals as additives when developing negatives. The pictorial result merges the results of light capture with earth processes. These sometimes anarchic analogue processes are, at times, a welcome break from our all-pervasive digital world.

For Hawker’s art, four concepts overlap. The first is a desire to connect with nature. The second is that nature can be a co-creator. The third is that humans cannot control nature. The fourth is that landscapes embed our history. To reflect these concepts, Hawker adds local salt to photographic emulsions during the development of negatives.

“Salt” represents a jump step in Hawker’s ongoing creative development. The large scale prints are dramatic. The continuity is provided by the conceptual underpinnings along with the technical evolution of the salt application. Does the above always work? In an important sense, this should not be an expectation.

Sometimes, nature does the unpredictable thing. The results may have a somewhat schizophrenic look to them: the landscapes may look extremely real and extremely not real at the same time. The juxtaposition of crystal-scale marks with sweeping landscape scale light capture tends to create dual visual realities.

Hawker’s particular gift lies in unifying these elements pictorially. When it all comes together as in “Voices [Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre], 2022”, “Mount Gulaga, 2021” and “Dark Crystals, 2021”, Hawker’s works are major artistic achievements.

The art works are complemented by Hawker’s workbook which is well worth a fossick in its own right. A set of negatives give us intriguing insights into what things look like part-way through the process.

To capture her landscapes, Hawker travelled from the south coast to Kati Thanda – Lake Eyre. Where feasible, she connected with indigenous traditional owners. She physically and spiritually immersed herself in the landscapes.

Hawker’s landscapes conform to one dominant theme in contemporary Australian landscape photography. Most such images are depopulated. There are occupation middens on the shores of the lake. For Australian landscape photographers, putting people back into landscapes seems to be something of a major creative challenge. Would they be tourists? Would they be pastoralists? Would they be miners? Would they be the traditional owners? Would they be a mix of all four?

Hawker’s works are held in numerous institutional and private collections. Hawker won a Canberra Critics Circle award for photography in 2021. She won the Mullins Conceptual Photography Prize in 2022. The “Salt” opening night crowd of 200 was booked out. Judging by the multiple clusters of red dots, “Salt” is a major commercial success.

It is a great pleasure to see Canberra-based Sammy Hawker’s career flourish. — review by Con Boekel.

Australian Photography Journal

11 jul. 2022

Mount Gulaga, 2022, archival photographic print from4x5 negative processed with ocean water (Walbunja Country).

Winner of the 2022 Mullins Contemporary Photographic Prize & acquired by Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre.

The Australian Photographic Society (APS) has announced Canberra-based photographer Sammy Hawker as the winner of the 2022 Mullins Contemporary Photographic Prize (MACPP) for the work titled Mount Gulaga.

This year's judging panel included Heide Romano, Alex Wisser and Bill Bachman. Hawker's work was selected as the overall winner from the competition's largest pool of entries yet. This year saw 260 submissions come in from 134 different entrants. As winner, Hawker takes home a $15,000 cash prize and Mount Gulaga will become part of the Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre’s permanent collection of post-war contemporary paintings, ceramics and photography.

The concept statement for Mount Gulaga reads:

"This work was captured on 4x5 film looking out towards Mount Gulaga from the Wallaga Lake headland. I processed the negative with ocean water collected from site. When processing film with salt water, the corrosive properties lift the silver emulsion and the representational image is rendered vague. However, an essence of the site is introduced to the frame as the vibrant matter paints its way onto the negative. A ghost of Gulaga looms behind the abstraction ~ felt rather than seen."

The works of all 30 finalists are now on show at the Muswellbrook Regional Art Centre. The exhibition is open from today and is set to run until 27 August 2022.

Canberra Times

review of Portrait by Brian Rope

7 jun. 2022

CANBERRA photographer Sammy Hawker challenges the notion that a photograph constitutes the moment that a shutter is released. She explores ways of making, rather than taking, images.

Over the past six months, she has worked closely with nine young people from headspace Tuggeranong, exploring ways they could co-create photographic portraits. Part of the City Commissions project delivered by Contour 556, one of seven artsACT initiatives in the Creative Recovery and Resilience Program, the works are now displayed around Tuggeranong Town Centre.

Hawker wanted the project to be em-powering. One where there was no right or wrong, and where the final photographs celebrated identity and experience beyond just the way her subjects looked in the frame. It was an opportunity to realise we always have some choice whether we repress difficult experiences.

headspace is a safe space that welcomes and supports young people aged 12 to 25, their families, friends and carers, helping them to find the right services. Learning the headspace motto "clear is kind", Hawker realised her project was also about finding clarity as a form of self-compassion - shining light on what for many was a particularly dark and confusing time.

The portraits of the young people are captured on a large format film camera. Commonly, in photographic practice, touch and marks on negatives are to be avoided. But Hawker invited her subjects to handle, manipulate, scratch or even bury negatives in order to introduce something of them-selves. The young folk wrangled puppies, dived into rivers, got dressed up, sprinkled bushfire ash on negatives and processed film in the Headspace carpark.

Each participant was invited to use the project to reflect on their experiences of difficult times. Their statements relating to the images reveal resilience and hope. Chanelle reflected about living in the mo-ment. The negative of her portrait, showing her immersed in the Murrumbidgee River, was processed with water from that river, ocean water and permanent marker.

Sophie spoke of learning to embrace everything in life. Her portrait's negative wa processed with bushfire ash and the word "embrace" scratched into it. The ash creates a frame that embraces her. Sanjeta really likes her photo with jellyfish manipulations as metaphors for how she now goes with the flow of her life journey. Her expression conveys a "so be it" attitude. The negative was processed with Murrumbidgee water, rainwater, seaweed and chemical stains.

Ray wanted to keep connected and bring some joy into the lives of others. The portrait's beaming smile conveys joy. The idea of processing the negative with Whiz Pop Bang bubble mixture and wattle pollen adds to the joy. Jazzy is photographed with her much loved dog Milo. So, of course, the processing of the negative utilised Milo's pawprints. — article by Brian Rope.

Canberra Times

review of Acts of Co-Creation by Brian Rope

7 jun. 2021

Sammy Hawker is a visual artist who was noticed early when one of her works was selected for the 2010 Capture the Fade exhibition. Since then, Hawker has achieved a Bachelor of Visual Arts at Sydney College of the Arts, had a solo exhibition Dieback in 2019, participated in the ANU School of Art & Design Bundian Way Arts Exchange last year, and received an artsACT Homefront grant to complete a body of work.

She is a current recipient of the PhotoAccess Dark Matter darkroom residency program, with an exhibition in the Huw Davies Gallery scheduled for later this year.

The works in this exhibition have been created in Yuin Country, Ngarigo Country, and Ngunawal Country. While visiting each site, Hawker took a few rolls of film and collected small samples of water, soil, eucalyptus bark and flowers. The show features a stunning collection of works employing pigment inks, emulsions and silver nitrate.

In her process statement for the exhibition, Hawker speaks of time defined by silences - whilst standing in a once-familiar landscape while the ash of a torched ecosystem floated through the air; looking in awe at critically endangered snow-gums; living alone in a city under global lockdown. She reveals that silences led her to practise more active listening; that the exhibition results "from recognising and celebrating the quieter but no less potent agency of the more-than human".

Hawker also speaks of a newly formed relationship with Ngunawal custodian Tyronne Bell. As a non-In-digenous Australian, she reached out to Bell to learn more about the sites she was working with. Walking with him on Country helped her see more. For each print, we are told what indigenous land it was created on. There are a few traditional landscapes, some composites, and many that reveal their negatives having been processed in solutions that include a variety of waters containing diverse elements.

When processing films, Hawker uses waters collected from the sites where the films were exposed. So, salt fractals form across works created with ocean water, whilst ripples appear on photographs developed with muddy lake water. Storm clouds photographed from Mount Ainslie were developed with rainwater that fell later that day.

Experiments with the technique of chromatog raphy add another aspect to the exhibition. Hawker mixed samples of matter with sodium hydroxide looking for the substance "to visually express itself over filter paper soaked with silver nitrate". She says, "Acts of Co-Creation are never predictable, and the resulting images can be both unsettling and thrilling. To me the image becomes alive; humming with the presence of the site itself."

Much background information is provided - about snow gums being affected by dieback; about how and why a water bowl tree was created to store water.

A centrepiece of the exhibition, Ngungara (Lake George) #1, was taken after rains had temporarily filled the lake. Ngungara means 'flat water' and the lake is a significant site for the Ngun-awal. From a roll of medium format film, it was processed with a jar of muddy water collected from the edge of the lake.

Also displayed is a collection of the bottled waters, plus seaweed film developer and such things as casuarina pods, ground up bark and lichen. It is an excellent exhibition that I spent a lot of time taking in. I was delighted to see that many works had been sold, some of the proceeds benefitting Aboriginal corporations in the Yuin, Ngarigo, and Ngunawal Countries. I congratulate the purchasers and Hawker, and strongly recommend readers to visit this exhibition. — review by Brian Rope.

Region Media

review of Acts of Co-Creation by Genevieve Jacobs

23 jun. 2021

“When everything breaks down, there’s a point where it also breaks open,” says photographer Sammy Hawker. She’s talking about the effects of COVID-19 on her arts practice, but she could just as easily be referencing her immersive works, created by lugging a film developing kit to the bush or the beach and processing her negatives using elements she finds on site.

Seawater and its corrosive effects, rainwater from the top of Mt Ainslie and muddy water gathered from Lake George play a part in creating striking images for Acts of Co-Creation, her solo exhibition at the Mixing Room Gallery in Griffith. Fractals and crystals form on works made at Twofold Bay, Rosedale and along the Bingie Dreaming Track. Seascapes, black cockatoos, scribbly gum tracks, high country streams and cicadas create a tapestry of images made with, and by, the things of the earth.

Samples of earth and eucalyptus bark are mixed with silver nitrate so “the visual expression of vibrant matter becomes apparent”, and Hawker displays her materials in the show too, including bottled waters, seaweed film developer, casuarina pods, ground-up bark and lichen. A massive image of rocks rising from shallow waters of Lake George, called Ngungara, was created from a roll of medium format film and processed to reveal an image of shimmering power.

A cinematographer before COVID-19, Hawker had plenty of time to reflect and walk when the pandemic hit. Daily walks on the O’Connor Ridge prompted deep thinking about the earth and representing it in a meaningful and beautiful way. Locked out of Photo Access (where she currently has a residency), Hawker began developing images in her laundry and on-site. As lockdown began to ease, she reached out to traditional owners, including Tyronne Bell, who took her into the bush and talked about its stories.

All works in the exhibition carry an acknowledgement of the country where they were produced, and a share of profits from works sold will go to three Aboriginal corporations who work on Ngunnawal, Yuin and Ngarigo country. “I would take the black bag developer and water, a stop bath and fixer with me”, she says. “I even lugged my scanner to campsites with power, like Depot Beach at Murramarang. I’d develop the negatives and hang some string at the campsite for them to dry.”

On other shoots, Hawker would rig up a DIY developing suite in country motel rooms, using a hairdryer on the negatives. Since the elements she uses can often be corrosive, judging when they’re finished is a fine art. Hawker would originally stop when there were a few salt marks, some intriguing patination on the negatives. Now she’ll push the process much further on some works, to the point of abstraction.

“Dark Crystals was about half an hour away from disintegrating completely, but it would never have become such an interesting work if it wasn’t in the water for so long,” she says. “Process to me is just as important an outcome. I find the works really interesting because they don’t often feel finished. They’re framed and static on the wall but have a potency to them because the landscape is literally inside them. I’ve taken away some agency as an artist and given it to the landscape itself.”

The show has an undertone of sadness, created in the aftermath of the Black Summer, drought, hail and the pandemic. Hawker admits it’s a reminder of how much we have to lose from alpine snow gums to pristine beaches. But her own thinking has changed about what that means. She says humans need to be conscious of the change we’re wreaking, but focusing on landscapes as dysfunctional is anthropocentric in many ways.

“Landscapes are regenerative. The world’s landscapes will be fine with their own systems and order, however we feel about it,” she says. “Throughout this show, there are key messages of listening to traditional custodians on how country works. It’s about active listening – stopping and trying to become more aware of quieter frequencies and symbiotic relationships that exist all around us.” — review by Genevieve Jacobs.

Region Media

review of Dieback by Genevieve Jacobs

27 may 2019

A devastating swathe of dead trees across two thousand square kilometres of the Monaro prompted Michelago artist Sammy Hawker’s video installation at the Photo Access Gallery, Dieback. And to watch the video is a haunting and sobering experience: ghostly, brittle limbs rise, white and bleached out of the Monaro mist. Lingering shots unfold across a landscape starved of shelter and punctuated by death.

Hawker is also a commercial video maker and has a long history of making work about how climate change is affecting the world in expected and unexpected ways. When she moved to the Monaro with her partner, she was struck by the impact of the dieback that began around two decades ago. Ecologists believe that the dominant Monaro species, eucalyptus viminalis underwent a major stress event they haven’t been able to pinpoint, perhaps in the 1990s or the first decade of the 21st century. The stressor may have been drought, changing land use, possibly even the end of indigenous cool burning practices.

Whatever the cause, it’s believed that the tree’s immune and stress responses were compromised, then tapped by a native eucalyptus weevil which healthy trees can withstand. The weevils destroyed nitrogen-rich lower leaves and the trees starved to death. While other species have survived, local viminalis populations have been all but exterminated. For Hawker, the trees and their mysterious deaths became a symbol of the speed at which the natural world is changing and how uncertain our fate is. “My role as a visual storyteller/artist is to spread this message in a way that’s more than just the facts. We need to provide emotion too,” she says. “The video is very dark, almost post-apocalyptic, to show how much we have to lose. You see the dead trees in order to understand that we shouldn’t take for granted what we have.”

Shot mostly in winter, colour levels are low and unsaturated and the images unfold at a deliberately slow pace. “When I’m doing commercial work, the shorts are shorter, more communicative. These shots are intentionally very long and abstract to draw the viewer in to a different state of consciousness, a meditative state that slows people down.” The soundtrack to the visuals comes, remarkably, from NASA’s recordings of the electromagnetic vibrations from various planets. Hawker has used the Earth tracks, which sound like white noise with blips and evoke a lifeless vacuum.

“When ecology is out of balance, the landscape becomes dysfunctional,” she says. “I tried to exercise that sense of aloneness, the uncanny feeling of a world we know but one where we couldn’t comprehend how we humans could continue living there. The point is that the planet is changing, in some ways, it’s becoming a new earth. More extreme weather will happen over the next few years and we can’t predict or have any idea what will happen as a result.”

While Hawker says the message can feel grim, her work is more about putting the risks into perspective. Dieback has engaged with Landcare volunteers and scientists working on the dieback to understand not only why it happened, but how the damage can be ameliorated. “It’s frustrating for scientists that the dieback wasn’t noticed early enough, so they are all on the back foot.” Hawker’s given hope by projects like the Atlas for Living Australia, a community science initiative that encourages users to register and record changes they notice in their environment. She’s also been involved in the Greening Australia comeback project which plants trees and identifies biodiversity hotspots with Monaro landowners.

“We can’t learn nothing from the dieback,” she says. “There can be a positive outcome from this as communities come together in the region. We have to urgently spread the message about making the switch to renewables and think about the earth as a key policy fundamental.” — review by Genevieve Jacobs.

Copyright © All rights reserved.